Is Rust a worthwhile companion for game devs? To test this, we create our own server for a game in Godot

This is a legacy blog post from a long time ago.

It might contain outdated or incorrect information.

I really enjoy creating games but when it comes to games, there is always one daunting task that game devs are scared off, online multiplayer. As soon as anything touches the web, it suddenly becomes a technical challenge to implement properly, esp. lobbies are among the worst contenders given that you somehow gotta exchange data between all clients.

The enormous upside however, is that multiplayer games are the games I tend to come back to much oftener than singleplayer games. One of my most favorite party games is probably Jackbox Party Pack, a game where each client connects to a centralized server.

The Beginning

One night I had a quite random thought, what if I created my own jackbox. I spend the entire last year learning Golang as I usually try to at least create some sort of proof of concept application for nearly all fields a language specializes in order to fully understand all it’s mechanics. This year I decided to undergo this process with Rust, a language I have grown to love really quickly as you can see by my blog post about cross compiling or embedded programming, as such, it only made sense to try to create my reimplementation in Rust.

However, as much as I love Rust, I gotta admit something, in terms of GUIs, it is still quite extremely lacking behind other programming languages. Like, there are many great libraries for it already but given that this should be a proof of concept server for an actual game, I decided to use Godot, a contender for the spot of Unreal and Unity in the game engine world, as the frontend.

Me using my entire brain power to decide what to use in my simple proof of concept game

Given the fact that this project would have had to have 2 different codebases for front- and backend I did not mind either way and this provided me with a great opportunity to work with Godot once again.

Another thing I decided was that the server should be nearly stateless. This gave me a great excuse to improve my knowledge about database integrations and also meant that the server would be much more performant, since y’know, it didn’t have to store anything in memory for longer than a few seconds.

I honestly had a hard time picking the right DB. I knew that most of the stored data would be temporary either way and I did not want my database to slow anything down. I also like the key & value system hashmaps or python dictionaries offer. As such, Redis was a natural contender.

WSL Madness

This section is probably not that interesting for people that are smart enough to simply use normal linux. But those who are monkey brain such as me, did you know that you can easily start systemd services in WSL through some m a g i c. The magic in question is Genie. Even though I use WSL for nearly all my projects, this was honestly the first time I required something to be run as a service, that being my DB -> Redis, as such, this was the first time I was required to actually use systemd.

Thanks to the techniques Genie uses, you can simply execute “genie -s” in any WSL terminal and create a proper environment to start redis in and sure enough, even though it took some while for me to figure it out, it works quite flawlessly.

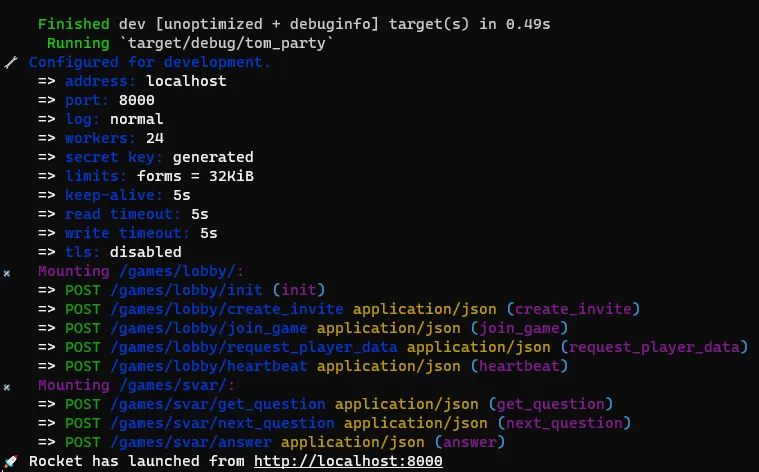

Rocket, Hyper, Warp or ActiX

Rust has a lot of different web frameworks and to be honest, it was kinda overwhelming and while I later regretted my choice, I chose Rocket as my web framework for this project. Rocket is easy to use, like, really easy to use. The syntax is so unimaginably easy to understand and boilerplate-free that it is honestly a blessing to work with it and the community support for it seemed good enough too.

Most of the boilerplate is hidden behind really easy to use macros, which is probably one of Rust’s strongest features. Even though I would love to tell you about their amazing features in more detail, I am way too underqualified for that. If you actually want to read blog posts from somebody that understands them in great detail, I’d recommend the blog posts by the macro king jam1garner.

To get started with Rocket, all you need to write is literally just this:

#![feature(proc_macro_hygiene, decl_macro)]

#[macro_use] extern crate rocket;

#[get("/<name>/<age>")]

fn hello(name: String, age: u8) -> String {

format!("Hello, {} year old named {}!", age, name)

}

fn main() {

rocket::ignite().mount("/hello", routes![hello]).launch();

}

Creating the backend

This blog post is already big enough as it is, if I were to explain each API point I created, it’d probably be another 1000 words of me rambling. As such I’ve decided to simply explain the structure of each endpoint. For more informations about all the endpoints, please read the README which I honestly spend too much time on.

Basically, each end point (except heartbeats) is a POST request to the server. The server knows nothing about the client and as such, the client has to authenticate itself with certain values inside the body. (Again, read the README for a much more detailed explanation).

The server then responds with a JSON that returns all the relevant information about the request. For example, if you create an invite code, the server needs to know the uuid of the game and the uuid of your user that you previously received. It then compares those values to data stored inside the Redis DB and returns the newly generated invite code back to you. The server never trusts the client with any data, as such it always requires a completely unique uuid token that only the correct client has in order to change data.

Game related data is stored inside a hashmap on Redis and always kept under a time limit in order to ensure that no unused data clogs the DB up. In order to ensure that game and user sessions are still valid and active, the server requires periodic heartbeats from each client which boil down to a simple “Is the player really who they claim they are?” on the server. Once again, Rocket makes handling this really easy:

use redis::Commands;

use rocket::http::Status;

use serde::Deserialize;

use rocket_contrib::json::Json;

use crate::db;

#[derive(Deserialize)]// Through this macro, rocket knows what data to expect and how to apply it to the following struct

pub struct Heartbeat { // These are the information the server needs from the user in order to ensure the user is who they are

uuid_game: String,

user_id: String,

username: String

}

#[post("/heartbeat", format = "json", data = "<data>")]

// This macro simply tells Rocket that we want to listen to post requests for

// this function at <mount_point>/heartbeat and that the data we receive should

// be a JSON and that the JSON should be parsed into the the data parameter of the function

pub fn heartbeat(data: Json<Heartbeat>) -> Status {

let mut con = match db::init_con() { // Connect to the Redis DB

Ok(con) => con,

Err(_err) => return Status::InternalServerError

};

let uuid_user: String = match con.hget(format!("{}:players", &data.uuid_game), &data.username) {

Ok(u) => u,

Err(_err) => return Status::InternalServerError

};

if uuid_user != data.user_id { // If the user isn't who they proclaim they are, we return without renewing the data

return Status::Forbidden

};

let _: () = con.expire(format!("{}:players:{}", &data.uuid_game, &data.username), 3 * 60).unwrap(); // Renew session for another 3 minutes

Status::Ok // If everything worked, we let the user know through the 200 "OK" status code

}

Now we only need to mount the function in our main.rs which is literally just a single line of code:

fn main() {

rocket::ignite()

.mount(

"/games/lobby/",

routes![

// Other functions [...]

games::lobby::heartbeat::heartbeat

],

)

.launch();

}

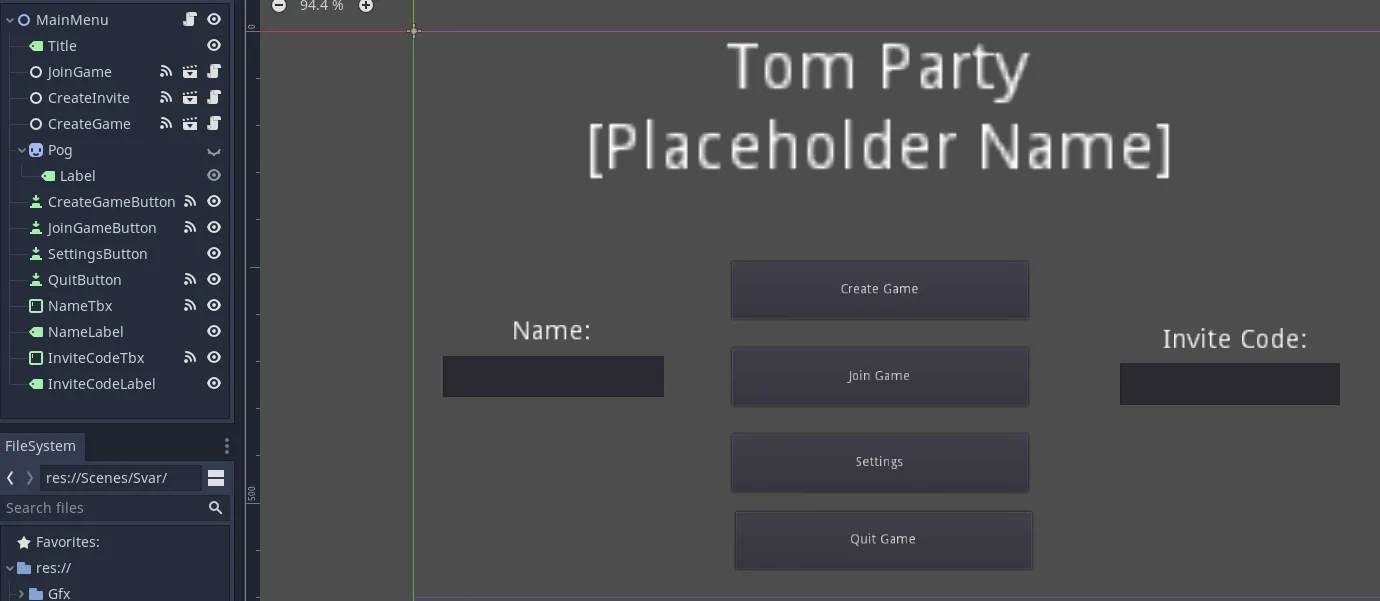

Using Godot as the frontend

Godot uses a scene system in which everything you see and interact with in either code or the UI is its own object and has to be loaded into the current scene tree. At first this is honestly a really confusing concept but the more you use Godot, the easier it gets to use, and it comes with many great upsides.

Let us look at our scene tree for the main menu:

Each UI element (The stuff with green icons) connects to some function in the code through a signal, such as when it is pressed or text is changed. For example, the JoinGameButton button executes this when pressed:

func _on_JoinGameButton_pressed():

$JoinGame.JoinGame()

$JoinGame refers to the “JoinGame” object in our scene tree, which is its own scene with 2 objects, a neutral node object (basically a dummy object) and one HTTPRequest object. Yes, even HTTPRequests are completely independent objects that need to be spawned into the scene and connected to some signal.

In this case, we ask the HTTPRequest object called JoinGameRequest to please make a POST request:

$JoinGameRequest.request(

global.server_url + "games/lobby/join_game",

global.user_agent + global.content_type,

global.use_ssl,

HTTPClient.METHOD_POST,

JSON.print(request) # Jsonify the request dictionary (identical to Python dictionaries) and then send it as the body

After it is done requesting the content, it will then respond to the function connected to it’s request_completed signal and which point we parse the server response and emit our own signal to the main menu which tells the main menu that we’re done joining the game and it is now able to switch the scene to the lobby screen.

func _on_JoinGame_joined_game(worked):

if !worked:

print("Couldn't join game!")

return

global.goto_scene("res://Scenes/UI/Lobby.tscn") # A user-created function is called that switches our scene to the lobby screen

If everything works, it ends up looking like this:

Removed video due to privacy concerns

Nearly 1700 words and we only explained 1 backend and frontend implementation out of more than 6 API functions needed to get to this point :)

Conclusion

Game servers are amazing to work with, it feels really interesting to work on two different code bases that are so tightly dependent on each other and yet again so extremely different. I really enjoyed my journey with this project and it once again taught me a lot about Rust.

I have never focussed on a single project in a dev-blog kind of style in any of my blog posts so I hope that I still managed to make it enjoyable to read this post.

If you have any questions (or want to follow me on social media), feel free to visit my Twitter.

Lastly, I want to thank all the new readers. Even though I don’t track traffic through Google analytics or similar tracking software, the twitter impressions alone showcased a viewership that I never could have imagined receiving. I humbly thank all of you.